One near-term outcome of AI’s impact on open source EDA is that I’ve been revisiting and enhancing some of my older projects. PyUCIS, a set of tools for working with verification coverage, is one of those. Over the next few posts, we’ll look at the impact AI is having on both EDA developers and users via this project.

Verification and Coverage

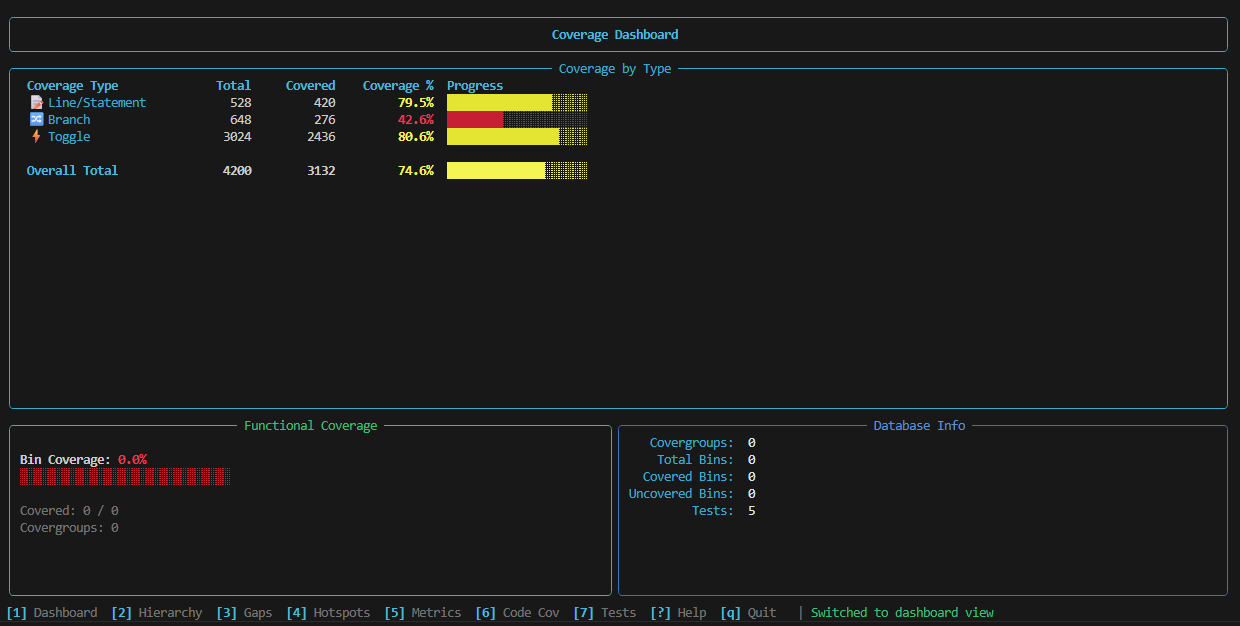

Coverage is a key metric we use to evaluate how well-verified a design is. We collect and analyze code coverage to identify areas of the design that aren’t exercised. We use assertion and functional coverage to ensure that key conditions are exercised. Combined with the right meta-data, such as test name, we can derive higher-level information such as a small set of tests that will exercise a design change.

Many design verification tools and frameworks support capturing and working with coverage metrics. For example, cocotb-coverage and AVL each support capturing functional coverage data, saving it to a file, and performing post-processing. Verilator supports capturing code and assertion coverage, and the major EDA companies have solutions as well.

But, all of these are independent. How can I view and analyze Verilator code coverage and AVL functional coverage together?

Standards: UCIS

A unique aspect of verification coverage is that we have are larger set of metrics than software projects typically use. Software projects tend to focus on code coverage, while design verification is also interested in functional coverage, FSM coverage, and assertion coverage.

Back in 2012, the Accellera EDA standards body released UCIS, the Unified Coverage Interoperability Standard. UCIS defines a data model and an API for interacting with all the types of coverage data that verification engineers work with. It also defines an XML interchange format supported by some tools and the FC4SC library that implements functional coverage for SystemC.

Having a common API enables the classic separation of concerns that other common APIs, such as LSP and MCP enable. Instead of developing analysis capabilities for each and every coverage format, we can create tools that use the UCIS API, and converters to map coverage formats into the UCIS data model.

Open Source: PyUCIS

I initially created the PyUCIS project because I needed a way to work with coverage data captured by the PyVSC library that I was also working on. At the time, I focused on support for functional coverage (coverpoints, cross-coverage, etc) since that was the data PyVSC produced.

As I noted in the introduction, AI-driven productivity gains have me revisiting projects like PyUCIS to add new features and provide more-comprehensive support. But, also, to ensure that the libraries are properly AI-enabled for users. We’ll cover some of these new feature areas in future posts, but this post focuses on AI enablement.

Three Levels of AI Enablement

I’ve gradually come to apply a three-level approach for enabling a tool for AI agent access that reflect successively-deeper levels of integration with the tool.

AI-Friendly CLI

The first level of integration is via the command-line interface (CLI). AI agents, such as Copilot, Codex, and Claude Code, excel at using command-line tools. Best practices for enhancing the CLI to be AI-friendly include:

- Providing granular data-manipulation commands with good help messages

- Providing JSON output

- Providing a pointer to a SKILL.md file

In the case of PyUCIS, our primary interest is in enabling an AI agent to analyze

coverage data, so we focus most of our efforts on the show sub-commands.

usage: ucis show [-h]

...

positional arguments:

summary Display overall coverage summary

gaps Display coverage gaps (uncovered bins and coverpoints)

covergroups Display detailed covergroup information

bins Display bin-level coverage details

tests Display test execution information

hierarchy Display design hierarchy structure

metrics Display coverage metrics and statistics

compare Compare coverage between two databases

hotspots Identify coverage hotspots and high-value targets

code-coverage Display code coverage with support for LCOV/Cobertura formats

assertions Display assertion coverage information

toggle Display toggle coverage information

options:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

LLMs often work more effectively with JSON data vs unstructured

(or, arbitrarily-structured) text. JSON data has a regular structure and

associates meta-data with various elements of the output (eg ‘name’, ‘id’, etc).

In addition, an LLM can leverage tools like jq to efficiently slice and

dice it. Consequently, it’s a very good practice to support JSON output.

Enabling this with a specific switch is fine, since most humans won’t want

to see JSON.

Agent Skills is an emerging standard for providing instructions to agents.

======================================================================

PyUCIS AgentSkills Information

======================================================================

Skill Definition: /home/.../ucis/share/SKILL.md

Note for LLM Agents:

This file contains detailed information about PyUCIS capabilities,

usage patterns, and best practices. LLM agents should reference

this skill to better understand how to work with UCIS coverage

databases and leverage PyUCIS tools effectively.

For more information, visit: https://agentskills.io

======================================================================

A skill for a tool provides examples and more in-depth

instructions on tool workflows. I like to advertise how to find the

tool’s skill in the help message, since AI agents often check this first.

Model Context Protocol

The Model Context Protocol (MCP)

is a JSON RPC-based communication protocol that allows AI agents to run external operations.

MCP excels in situations where operation setup times are long. For example, loading a waveform

database often takes significant time. The overhead of doing so every time the Agent wishes

to look at a waveform value is prohibitive. A waveform MCP server, such as

pywellen-mcp, loads the waveform database once and

allows the Agent to perform many queries.

PyUCIS provides a MCP server with a range of tools, including:

Database Operations

- open_database: Load UCIS databases in XML, YAML, or UCIS binary formats

- close_database: Clean up database resources

- list_databases: List all currently open databases

- get_database_info: Retrieve database metadata and statistics

Coverage Analysis Tools

- get_coverage_summary: Overall coverage statistics by type (statement, branch, etc.)

- get_coverage_gaps: Identify uncovered or low-coverage items with configurable thresholds

- get_covergroups: Retrieve covergroup details with optional bin information

- get_bins: Detailed bin-level coverage with advanced filtering capabilities

- get_tests: Test execution information and results

- get_hierarchy: Navigate and explore the design hierarchy

- get_metrics: Advanced coverage metrics and analysis

Advanced Features

- compare_databases: Compare two databases for regression analysis and coverage deltas

- get_hotspots: Identify high-value coverage targets for optimization

- get_code_coverage: Export code coverage in multiple formats (LCOV, Cobertura, JaCoCo, Clover)

- get_assertions: SVA/PSL assertion coverage details

- get_toggle_coverage: Signal toggle coverage information

Given the speed of the PyUCIS SQLite database, I’ll be interested in point at which using the MCP server becomes beneficial.

API

An API provides an AI agent the most-detailed access to a tool’s capabilities. Both the difficulty of producing an API and the difficult of an AI agent using it depends heavily on the tool’s implementation language. For example, Python is often fairly easy on both counts, since producing an API typically means documenting functions that we’ve already created to implement the tool, and AI agents can simply load the module and go. On the other hand, a compiled languages like C/C++ will likely require explicit action to define and expose an API, and AI agents will need to use the language toolchain to compile, link, and run with the API.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Design verification heavily relies on good coverage data to assess completeness, and AI can play a critical role in analysis. PyUCIS implements the Accellera UCIS API, and supports AI agents via the CLI and a built-in MCP server. As previously mentioned, you can look at the AI-assisted workflow example in the PyUCIS repository to get ideas of how to work with coverage data using the PyUCIS library and AI agents. Next time, we’ll shift focus to look at some of the other new and improved features in PyUCIS that AI agents are helping to rapidly develop.