Transpilation and PSS

04 Feb 2025

You’re probably familiar with compilers. They take a high-level input description – typically a programming language – and distill it down to an efficient low-level implementation. Typically the implementation is machine code or bytecode. In other words, as close as possible to what will actually execute given the language ecosystem.

You might be less familiar with transpilers (or source-to-source compilers, as they are also known). Transpilers convert an input in one programming language to output in another programming language with a similar level of abstraction. Transpilers have been in use for a very long time. For example, the C++ language was originally implemented with Cfront, a transpiler that converted C++ input to C code that any C compiler could process. More recently, the Typescript and Javascript/ECMAScript ecosystems have used transpilation extensively to allow the languages to evolve while maintaining an impressive level of backward compatibility with older implementations of the language.

The next few posts will start to explore what we can do by transpiling test scenarios in PSS into implementations in existing programming languages.

Is PSS a Programming Language?

Both compilers and transpilers are software concepts, so it’s worth asking whether PSS language is a programming language. Portions of the language do provide the features of a standard programming language – if/else, loops, functions, and data structures. In this portion of the language, these constructs retain the same imperative semantics as the equivalent constructs in software programming languages.

The other major portion of the language has declarative semantics. This means that we focus on capturing the rules of our test scenarios instead of capturing how we will implement our test scenarios.

Why be declarative?

Take, for example, test scenarios that exercise a multi-channel DMA controller. When our test exercises multiple channels at the same time, it needs to use unique channels. With PSS, we can simply state that this is a rule: DMA channels are resources that can only be used by a single behavior at a time.

In contrast, if we are writing our tests in a regular programming language, we would need to design a channel-allocation algorithm to manage DMA channels for our tests. Actually, we would probably need several algorithms to handle all the corner cases that our tests need to cover.

The declarative nature of the PSS language increases our testing productivity by allowing us to capture the rules of our scenarios and automate the work of implementing tests.

Creating Model Implementations

Capturing tests in this way has huge productivity benefits. It also has a (subjective) downside: we need to use a constraint solver to evaluate the model and select the data and operation schedule that will be used to exercise the design. Constraints solvers are marvelous tools for ripping through reams of constraints, but they’re not considered fast when compared to the execution speed of regular procedural programming languages. In addition, constraint solvers typically require substantial resources to run.

This need to solve the PSS model to generate specific tests, along with different verification-platform characteristics, has resulted in two common ways to produce tests from a PSS model:

- On-the-Fly Solving - This model is typically used in simulation. A special PSS interpreter and constraint solver run in parallel with the simulation and make choices as they are needed.

- Pre-Run Test Generation - This model is typically used when the test will run on a processor core within the design. In this model, the entire test is produced as source code prior to the start of test execution. We want to keep the code that runs on the processor core simple for many reasons, and pre-solving the PSS model allows us to do this.

Both of these models are useful and important, but the on-the-fly model is very interesting because it suggests that we might be able to leverage the constraint solver within our SystemVerilog simulators to provide the solving needed to evaluate our PSS models.

Transpiling PSS to SystemVerilog

I’ve been working PSS infrastructure, in general, for a while. More recently, I’ve focused on using that infrastructure to implement the beginnings of a PSS to SystemVerilog transpiler.

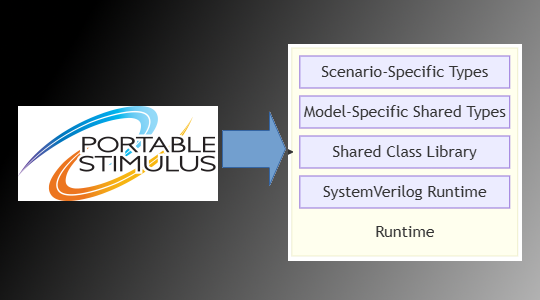

The general flow is shown below.

Specifically:

- The Zuspec-SV tool processes the PSS model source to produce an implementation for an Action

- It produces two SystemVerilog packages. The first contains types specific to the action being implemented. The second contains types shared across all actions captured in the model

- These packages are compiled along with a supporting class library and the user’s testbench, and executed by a SystemVerilog simulator.

A simple example

Let’s take a look at a tiny example from the Zuspec Examples project.

import std_pkg::*;

component pss_top {

action Hello {

exec body {

message(LOW, "Hello World!");

}

}

}You can find the soure here.

This extremely-simple PSS model prints ‘Hello World!’ to the simulation log.

Have a look at the root SystemVerilog module to see how the SystemVerilog model implementation is invoked:

module top;

import pss_top__Entry_pkg::*;

initial begin

automatic pss_top__Entry actor = new();

actor.run();

$finish;

end

endmoduleWhere do we go from here?

Transpiling PSS to SystemVerilog provides a useful interesting implementation option for PSS, both because of the solver within the simulator and because PSS is frequently used with UVM testbenches.

If you’re interested in trying out the PSS ‘Hello World’ example, have a look at the instructions in the README file.

The Zuspec-SV transpiler is under active development, but the approach

looks very promising. Over the next few posts, we’ll have look at

additional PSS constructs that we can implement in SystemVerilog and,

more importantly, see how PSS interacts the testbench and design.